This entry is an elaboration of a LinkedIn post I wrote in the spirit of spooky season.

There is something rather horrifying about the processes of extraction. The way in which the ground is forcefully struck, penetrated – invaded – by monstrous machinery through which raw oil is sucked and broken down, lends itself well to the gothic and horror narrative forms.

In petrocultures studies, there’s been rising interest in the petrogothic that explores the horrors of extraction. This can be the earth rising to haunt us, climate change framed as nature’s revenge, or ghosts of violated landscapes and exhausted futures lurking in the everyday. Not to mention the “resource curse” that dooms all resource-rich countries to economic stagnation and political instability.

I find ghosts to be a fascinating starting point in thinking about resisting extraction and extractivism. They’re mysterious, unquantifiable and essentially unknowable as they resist, and perhaps refuse, being mined for meaning or “made useful”. (I delve into this more in a journal article on anti-extractivism). If we think about it, we can’t really extract or make use of something that we don’t know much about, much less handle.

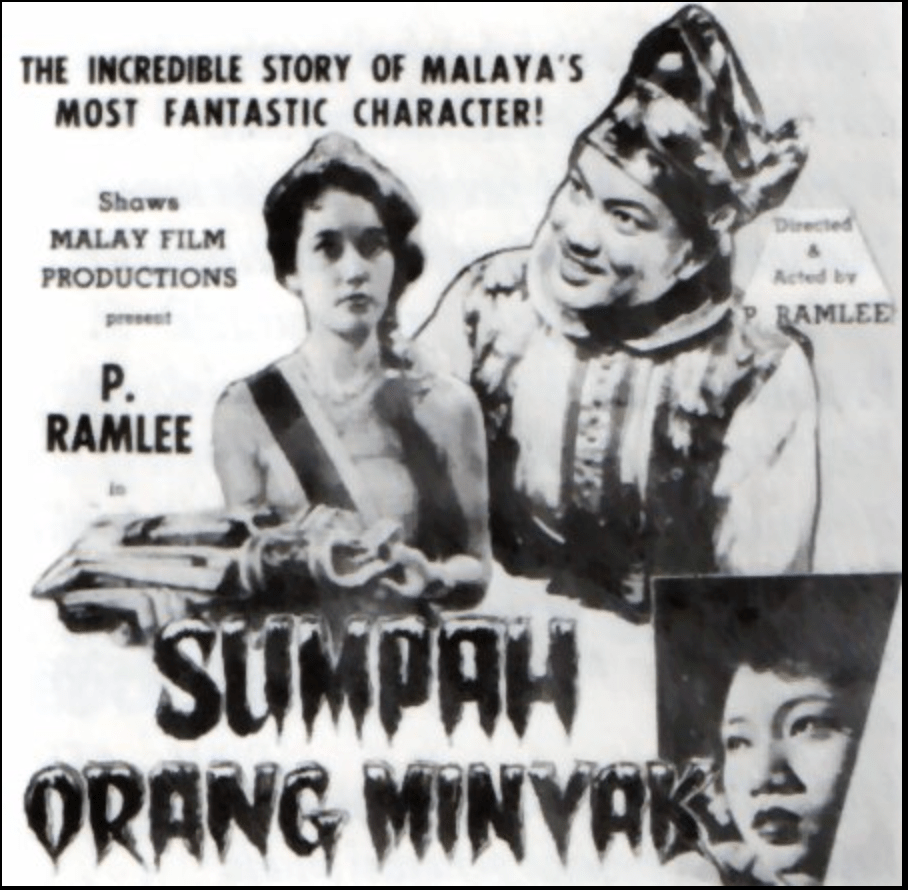

Take, for example, the figure of the Orang Minyak (the oily man) in Malay folklore. The Orang Minyak is a grotesque, male-seeming, human-like figure covered in oil who terrorizes women.

It/He came to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, especially in Malaysian and Singaporean films, coinciding with rapid urbanization (Yogesh Tulsi’s essay, ‘An Oily Mirror‘, is a great resource on this). The folklore took hold of local imaginations so strongly that the figure still features in contemporary tales such as Zen Cho’s ‘The Mystery of the Suet Swain’ in Spirits Abroad (2021).

While he can be read as representative of modernity’s ills, terrorizing kampungs, his slipperiness and evasiveness speaks to nature’s essential unknowability (and here I’m reminded of the umwelt).

If oil, as depicted by petrogothic stories, has its own ungraspable dimensions and perhaps even agency, how, then, does extraction occur and what facilitates extractivism?

One of the ways is through language. When we map, name, and categorize the earth, we make it familiar, i.e. manageable and extractable. Oil fields, for instance, are given friendly names to naturalise them in the public imagination. Scientific drawings and data charts render the planet legible, but in the process, perhaps strip away its spirit and more-than-human agencies. (I touched a little bit on this in my first post here).

Knowledge systems can be extractive too. They can overwrite traditional or spiritual ways of knowing, replacing them with supposedly rational and measurable ones. I’m thinking here of traditional ecological and Indigenous knowledge systems being marginalized by Western education systems. Or even the dominance of the STEM subjects over the humanities.

An example of these competing epistemologies emerges in G.C. Harper’s accounts of the early years of the oil industry in Seria. He tells a story about a crocodile catcher in Brunei who used “magical” methods to lure and capture crocodiles (with a chicken and some gold) – a measure that Western oil workers dismissed as superstition. Yet he succeeded where their techniques failed.

It’s a haunting reminder of how epistemic inequalities push out one way of knowing in favour of another and how even our knowledge practices can reproduce the logic of extraction.

To see the world as alive again and not just as material to be managed might be the beginning of a different (ghostly?) kind of literacy altogether.

Leave a reply to Reclaiming Water – Petro-Ambiguity: Environment, Energy, Culture Cancel reply